User’s Guide

to

the online version of

the Myers and Driscoll collections

of Popular Music of World War I

This brief guide is meant to facilitate research by persons interested in the culture of World War I and, in particular, the culture’s musical manifestations. The explanation below pertains to two online archives. These contain images of sheet music that are, of course, interesting and useful in themselves. But the presentation of these images and the metadata associated with them are meant to be a tool for research—a tool that can be applied in an indefinitely large number of ways to extract data, discover examples, and acquire new insights about the war years (taken to be 1914–1920) and the music created during and about World War I. That tool is best used together with a spreadsheet that contains much, but not all, of the metadata in a different form.

Each version of the metadata affords—and constrains—certain types of research. Neither the spreadsheet nor the explanation below is meant to impose research agendas or prescribe methods; they are intended simply to explain the capacities and peculiarities of the two versions, taken together, much like one might describe the attributes and potentials of a newly designed bread-maker. Please do create your own recipes.

The entry page

Browsing

Searching

The item pages

Envoi

The entry page

In all that follows, the Myers Collection will be used for illustration, and it might be useful if you opened the entry page for that collection now.

Figure 1, above, depicts that entry page; the Driscoll entry page is identical except that the descriptive text and image pertain to that collection. The top and bottom of the page are fixed as a header and footer that appear on all pages. The bottom gives links and details regarding the University of Illinois Library, the institution that houses both digital collections. The physical collections are, respectively, at the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music at the University of Illinois and at the Newberry Library in Chicago. Do note the contact information provided at the bottom, just above the blue footer; “contact us” opens an email link to write the library staff. If the website as a whole is perplexing or troublesome or prompts suggestions from you, those are the people to write; but if you have questions or, better yet, information about the sheet music and the metadata itself—about titles or individuals or publishers, for instance—it will more helpful for us both if you contact me, William Brooks, at w-brooks@illinois.edu.

In the center of the page is a summary of the Myers collection, and above it there are two boxes (red rectangle in figure 2). The box on the right (“Physical Collection”) takes you away from the digitized collection and to the finding aid for the physical collection. This can help if you ever need to see a title in person; you can specify the exact location so that the archivist can retrieve the material in advance of your visit. The box on the left (“934 Items”) opens the collection in browsable form, discussed below. On the right, above the image, is a search box (red oval in figure 2) that applies to this collection only. Searching, too, is discussed below.

The top of the entry page, above the red line, identifies the Myers collection as part of the Illinois Library’s Digital Collections. Links on the left (green rectangle in figure 2) take a user to lists of all the collections and to all the items in the collections. It’s worth investigating those collections, since for certain kinds of research they will be useful. Click on “Collections” and enter “entertainment” in the filter box near the top on the left. The “American Popular Entertainment Collection” appears. This is an immensely valuable resource, and the three periodicals digitized there were current during the years when this sheet music was published. Now click on “items” and enter “clipper” in the same filter box; the most relevant items, the website decides, are the digitized issues of the New York Clipper, which was, before Variety, the trade journal for show business of all kinds.

Return to the entry page, if you would. Above the red line and to the right, there is a search box (green oval in figure 2). This box searches all the digital collections. The Myers collection is among these, but a search in this box for a common word or phrase usually produces an unmanageable number of hits. Try entering “after the war” (in quotation marks to ensure it is read as a phrase) in that search box. You will get something like 769,344 hits, which is not much use at all. But on the left there are a series of filters: names of collections, creators, subjects, repositories, and so forth. Now check the box, under “Subject,” next to “World War, 1914 — Songs and music.” Those hits are reduced to 36 items; and these are exactly what you would obtain if you searched the Myers and Driscoll collections separately for that phrase. Thus, with a little strategic filtering, the “Digital Collections” search box allows both sheet music collections to be searched at once. This is useful.

Now delete “After the War” and insert instead “Alcoholic Blues.” You will have 315 hits, and the first one is for a piece of sheet music in the Myers collection. But directly under it is an article from the New York Clipper for 8 October 1919. Remember the page number (14) and click on the link. You will be taken to the pages in the “American Entertainment Collection” for that particular issue of the Clipper. Find page 14, click on it, and then click on the advertisement that is highlighted. “Alcoholic Blues” is highlighted in a sentence at the bottom of the page: “Performers without exception claim it’s as big a song as ‘Alcoholic Blues.’” You’ve learned something: “The Alcoholic Blues” (which was copyrighted in December 1918) was so successful that in October 1919 its publisher was still using it as a standard against which to measure new publications.

Not all searches will be as efficient or as simple as that one. But the ability to combine sheet music, trade journals, and even newspapers or photographs in a single search, filtering as necessary to eliminate irrelevant results, can be a very powerful tool in discovering the historical context in which an item of sheet music—or a person or a publisher—is embedded. And that has only been made possible by placing the Myers and Driscoll collections in a field of digitized artifacts, all of which are treated entirely equally by a single search engine. [top]

Browsing

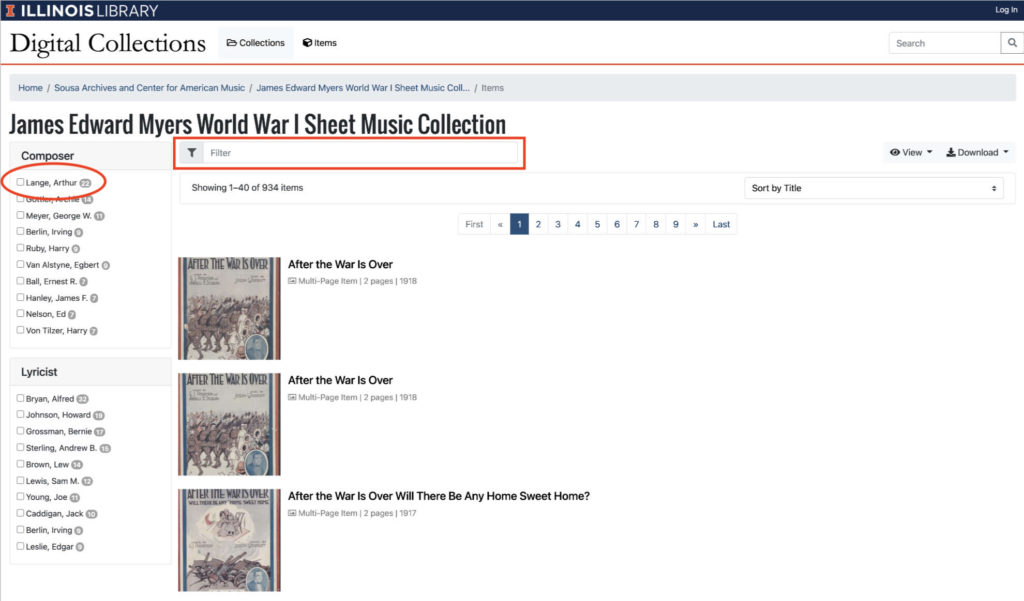

Find your way back to the entry page for the collection and click on the browse button (“934 items”). You are taken to a list of titles, each with a thumbnail image of its cover, and with a different set of filters on the left (figure 3). These work exactly as did the filters in the global search we did earlier; if you check the box for “Lange, Arthur” (red oval in figure 3) the number of titles listed is reduced from 934 to 22. This is equivalent to searching for the phrase “Lange, Arthur” or for the words Arthur and Lange (without any quotation marks). You can confirm this, if you wish, by returning to the entry page and entering those words in the search box above the image.

Browsing is straightforward; just work your way down the page, looking at whatever catches your eye. But at this point you may find it useful to download and open the spreadsheet, because certain peculiarities mean that titles are not treated quite alike there. First, the browsing page automatically disregards articles at the start of titles (“A,” “An,” “The”), as is conventional. Not so with the spreadsheet, which is distressingly literal about such things; hence “The Blue Star in the Window” on the browse page is “Blue Star in the Window, The” on the spreadsheet.

More importantly, the two platforms exercise different rules regarding punctuation. Excel (the platform for the spreadsheet) treats all punctuation as alphabetical characters, and orders entries accordingly. Thus, on the spreadsheet “America the Free” appears before “America, Here’s My Boy,” which appears before “America! My Homeland,” which appears before “America’s Crusaders,” which appears before “American Hearts.” In contrast, when sorting, the website disregards all punctuation including spaces; thus those titles would appear in the following order on a browse page: “America, Here’s My Boy,” “America! My Homeland,” “American Hearts,” and “America’s Crusaders.” This difference is usually of no consequence when browsing, but if a direct comparison is made between the spreadsheet and the browse page, it can cause confusion. And it has a more substantial effect when searching: for example, searches for “America! My” and “America, My” or “America My” give exactly the same results despite their different punctuation. [top]

Searching

On the entry page, searches are done using the search box. On the browse page, the terms are entered in the “filter” box on the left, above the thumbnails (red rectangle, figure 3). It is very important to realize that searches include all metadata, not just titles and personal names. Since lyrics have been entered for all texted music in the Myers collection (they are still quite incomplete in Driscoll), a search for a particular word will find all the items in which that word appears in the lyrics or in the title—or, for that matter, anywhere in the metadata. Hence the editorial entries under “comment,” “historical note,” and so forth are also searched. If one searches for “liberty loan” one finds a title with the phrase (“That’s a Mother’s Liberty Loan”), lyrics with the phrase (in “The U. S. A. Will Lay the Kaiser Away”), and a historical note with the phrase (for “Let’s Keep the Glow in Old Glory and the Free in Freedom Too”). This inclusiveness might feel like an irritation if you’re trying to find a specific item, but it is hugely useful if you are pursuing research into a topic, an icon, a quotation, or other concepts that were common to many contexts. Again: the metadata and the search mechanism is designed above all to further research, not to index materials for retrieval.

The search engine requires complete words; a search for <Calif> will not find appearances of <California>. But it does accommodate a wild card, indicated by an asterisk. Thus a search for <peace*> will locate 121 items that contain “peace” and 17 items that contain “peaceful.” Searches are Boolean, following modified conventions. Two terms entered without quotation marks are automatically joined by a Boolean “AND”; thus a search for the pair of words <Absence Solman> (with no quotation marks) yields titles in which both “Absence” and “Solman” appear in the metadata. There’s just one of those: “Absence Brings You Nearer to My Heart.” Quotation marks indicate phrases, in which both words have to appear in sequence; hence “Absence Solman” yields no hits whatsoever. The minus sign (actually a hyphen) indicates that a term must NOT appear in the metadata: the pair <Absence -Solman> produces the title “I Wonder If You Miss Me” because “absence” appears in the lyrics and Solman makes no appearance. Finally, a double pipe serves as a Boolean “OR”: thus the string <Absence || Solman> yields eight titles, some containing the word “absence,” others containing “Solman.”

Searches, in sum, are extremely powerful instruments that, properly used, can generate both data and historical insights. I encourage you to explore their potential, and to share your insights with others in the community of scholars. [top]

In coordinating the spreadsheet with the digital archive, the item numbers (columns A and B on the spreadsheet) are key. Each item number is unique, and since each appears in the metadata, entering an item number from the spreadsheet directly into the search box (figure 4) will generate exactly the associated image and metadata and no more. When working with a set of materials—for example, all the versions of a single title—use item numbers to keep things straight. Item numbers work both ways, too; one can extract the item number from the website metadata and then search the spreadsheet for that string. This is useful: for example, if a historical note indicates that the imprint being viewed is the third of four printings, and if you have questions about the other ones, the spreadsheet usually will provide at least some of the answers.

The item pages

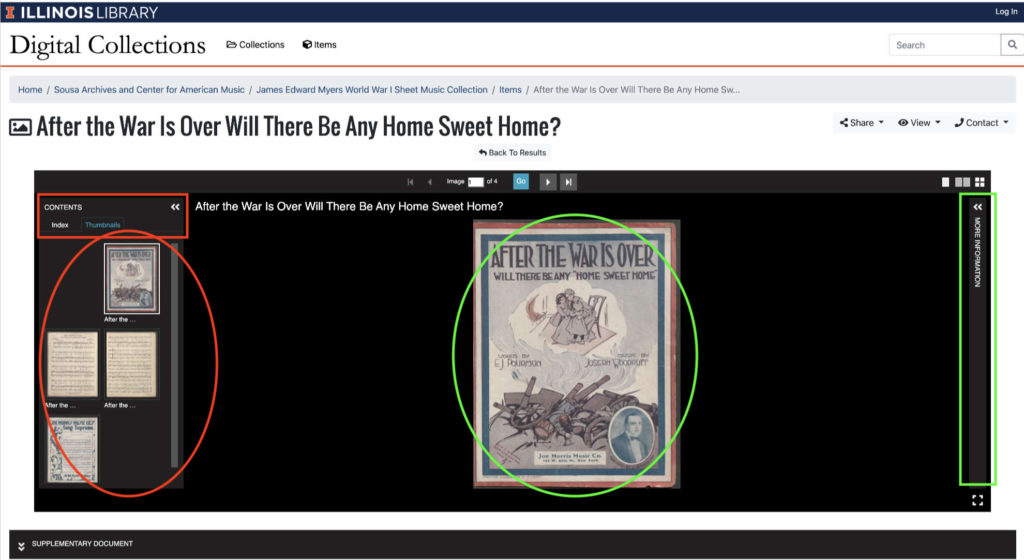

Try entering into the search field the item number from figure 4: 2014_12996_011. You should be seeing essentially the same page as figure 4 depicts. Now click on the thumbnail image or the title: you will see figure 5, or at least some portion of it. This is the item page, and all item pages follow a standard format. At the top are a set of images—thumbnails on the left (red oval on figure 5), the focal image on the right (green oval on figure 5). With the cursor on the focal image, try scrolling: this zooms in or out. Click and drag, and you can move the image as you wish within the window. Zoom in to see details—of the signature, bottom left, for example; zoom out to see the full image. Click on one of the other thumbnails and the focal image is replaced by that one. Explore the borders of the frame; these allow you to customize how much and what you are seeing. Information about the set of images appears on the left (red rectangle); metadata can appear on the right (green rectangle; click “more information”); tools for manipulating the image appear above the frame whenever your cursor rests in the window. Accessed in a bar just below the window is a “supplementary document”; this is a PDF transcription of the lyrics (see “History” for further explanation). Since the lyrics also appear in the metadata, you’ll rarely need to open this; but if you need to quote the lyrics at length, for instance, your task will be simpler if you download the PDF.

Scroll down the page a bit, and you will see something like figure 6. This is where the metadata appears; for a full discussion of the fields and their contents, see “Conventions.” You may have noticed that the the URLs for these pages—and all the pages in the digital archive—are quite long and not intuitive. The “Permalink” directly below the images (red oval, figure 6) allows you to copy the link with a single click (“copy”). Note particularly that certain entries have a magnifying-glass icon beside them (green ovals, figure 6). Clicking on these automatically searches the collection—just the Myers collection, in this case—for the metadata entered here. This is extremely useful when studying publishers or individuals, especially; you can very quickly see what other items in the collection are pertinent to the person or firm.

Now click on the green button (blue oval, figure 6), or just scroll to the bottom of the page and click on the plus sign next to “Download.” The page will open up and offer a range of download options. Each of these will serve a different purpose; the archival framework was designed in hopes that any user, needing an image for any purpose, would be able to generate an appropriate form of that image without having to employ a graphic design program post-download.

At the top (green rectangle, figure 7) are three options that provide a complete set of images for the entire item—four, in this case. “Zip of Masters” yields the four master images—extremely high-resolution and very large (in this case, over 2 GB). “Zip of JPEGs” provides just what it sounds like: four (in this case) separate images in JPEG format—good but not exceptional resolution. And “PDF” creates a single PDF file that contains all four images in sequence.

Below these are additional options for single pages (red rectangle figure 7). The two “master file” options are self-explanatory; but click on “Custom Image” for the top image (the cover page). A popup box appears, shown in figure 8.

This is a very powerful conversion tool, extremely useful if you need an image for a specific purpose. On the left a series of five boxes (red oval, figure 8) gives options for resolutions, from extremely high and large (100%) to very low and small. If one needs a super-high quality image—for use in a video, say, in which the “camera” will zoom in and in, smaller and smaller, to reveal tiny details—use the highest resolution. For a thumbnail used as a part of an index or catalogue, choose the lowest. And so forth.

But we’re not done! The boxes below (green oval, figure 8) allow you to convert the image, at the resolution you’ve chosen, from color (the default) to either bitonal (black and white) or gray (grayscale, in most printing circles). Are you publishing in a context that only accepts grayscale images? Then select “gray” at a good but not maximum resolution. Are you publishing a color insert in an edited collection? Then choose “color” and the highest resolution. And on and on . . . the intention is that the website will do the work for you, and you will be able to download precisely the image that you need. [top]

Envoi

And that’s it. We’ve discussed all of the options that this research tool affords. It remains only for you to use this tool—to test its limits, to explore its potentials, to devise unexpected applications, to . . . well, above all, to answer (and ask) questions. At the very bottom of the item page (yellow oval, figure 8) is a single, simple line: “Email curator about this item.” Click on it, and an email message will open, addressed to the Sousa Archives. The Archives will respond to you, of course, but they will also forward your message to me, because I want to know what you discover. I want to know your questions, your complaints, your confusions, and your triumphs. And if you want, you can bypass the Sousa Archives and write me directly: the address, again, is w-brooks@illinois.edu.

A world of insight awaits you. Enter that world, and enjoy all the creatures that inhabit it. They will be your playmates in what is, after all, a vast playground. Care for them—and for yourself. [top]